Most of the following information in this second part of the Frederick Douglass article is taken from his autobiography, My Bondage and My freedom.

Douglass eloquently and beautifully wrote down his hard story. His story is free of manipulative drama but full of soul. He wrote that suffering did not ultimately bring him to despair – it brought him to hope for a future when a person would not be bound under oppression because of their race. Douglass’s hope was so strong that he became part of the solution to slavery, spending most of his life in pursuit of freedom for his race. His story is one worth reading.

When Frederick and Anna left New York after they got married, they first went to Newport, RI. Here, they met two abolitionists who told them about New Bedford, which was one of the significant destinations of the Underground Railroad. Within just a few weeks of Douglass escaping slavery and getting married, he and his wife settled into New Bedford with a completely new landscape for life in front of them.

The Douglass’ were welcomed into the home of Nathan and Polly Johnson, African American abolitionists living at 21 Seventh Street in New Bedford. It was here that Frederick and Anna were encouraged to take the last name ‘Douglass.’ When Douglass arrived in New York, he changed his last name to Johnson to protect his identity, but he changed it a second time when Nathan Johnson suggested the name Douglass.

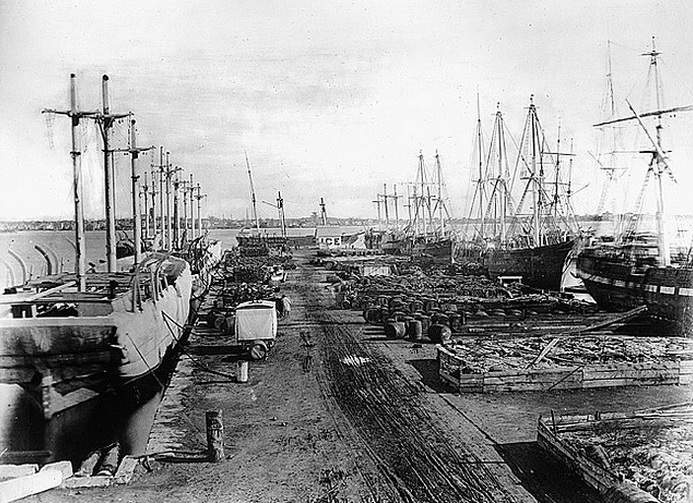

Douglass’s book My Bondage and My Freedom describes the scenes he saw on his first afternoon in New Bedford. He went down to the docks and as he watched the men at work he was surprised by what he saw. “On the wharves I saw industry without bustle, labor without noise, and heavy toil without the whip…there was no loud cursing or swearing…everything went on as smoothly as the works of a well adjusted machine” (351). He was also taken back by the wise use of animals to help with work. He took note that an ox worth eighty dollars was doing “what would have required fifteen thousand dollars worth of human bones and muscles to have performed in a southern port…everything was done here with a scrupulous regard to economy, both in regard to men and things, time and strength” (352).

Nathan Johnson assured Douglass that in New Bedford, black and white children went to school together, that a black man could hold any office in the state, and that no slaveholder could take a slave from New Bedford. This sealed Douglass’s assurance of his safety and he immediately set out to look for work. He found his first job three days after arriving in New Bedford and described his experience in these words: “It was new, hard, and dirty work, even for a calker [sic], but I went at it with a glad heart and a willing hand. I was now my own master – a tremendous fact – and the rapturous excitement with which I seized the job, may not easily be understood, except by some one [sic] with an experience something like mine…that day’s work I considered the real starting point of something like a new existence” (354).

His delight in finding New Bedford to be a place of such prosperous industries and economic wealth gave him hope of the new life he could live being his own master; he would have no one over him to take the money out of his hands that his own mind, sweat and muscle had earned. To him, this was a true manifestation of liberty. For years he had to endure watching every cent he worked for trickle out of his hands and be funneled to another person just to make their own life a little bit sweeter than it already was.

New Bedford held even more surprises for Douglass. Douglass’s sense of wealth and poverty came from his experience of life in the south. There, if a person had money, it was because they owned slaves – it was the work of slaves that brought money into the south. If white people didn’t own slaves, they were poor. Douglass described the white non-slaveholders as “the most ignorant and poverty stricken of men, and the laughing stock even of slaves themselves – called generally by them, in derision, ‘poor white trash.’”

Douglass wrote of his amazement in finding the laboring class of New Bedford living in houses “elegantly furnished – surrounded by more comfort and refinement – than a majority of the slaveholders” in Maryland. Of Nathan Johnson’s home Douglass wrote: “He lived in a nicer house…was owner of more books, the reader of more newspapers, was more conversant with the moral, social and political conditions of the country and the world, than nine-tenths of the slaveholders in Talbot County, Maryland” (350-51).

While Douglass made it perfectly clear through his writing that New Bedford was not fully free from discrimination and segregation (he found prejudice in workplaces and churches), he always ultimately remained grateful for the freedom he had found and the refuge he had in living in a state that did not allow ownership of slaves. Seeing discrimination in New Bedford did not set him back, though; he used it as a propeller to pursue total freedom for his race.

A few months after the Douglass’ arrival in New Bedford, a young man brought Douglass a copy of the Liberator, an abolitionist newspaper edited by William Lloyd Garrison. Douglass described the Liberator as “a paper after my own heart. It detested slavery…made no truce with the traffickers in the bodies and souls of men; it…demanded the complete emancipation of my race.” Through this paper, Douglass began to know the heart of the editor, Garrison. “Of all men beneath the sky, the slaves, because most neglected and despised, were nearest and dearest to his great heart” (360). From this point on, Douglass began attending all the anti-slavery meetings held in New Bedford, not yet realizing his own important future role in the fight against slavery.

In 1841, Garrison and others put together an anti-slavery convention in Nantucket. Douglass had taken no time off or vacation from his work since escaping slavery nearly three years before this. For the first time, he took a vacation to attend the convention. To his complete surprise, once he was there he was asked to speak. He described remembering very little about what he said except that he was shaking from nerves at the thought of speaking to a large group of people (1,000 were gathered).

At the end of the meeting Douglass was asked to become an agent for the Massachusetts anti-slavery society. He hesitated, feeling he was not prepared to take on such a position, but ended up accepting. He wrote that he was often introduced as having “…my diploma written on my back” (363).

This was the very beginning of Douglass’s launch into his work for the abolition of slavery. While living in New Bedford opened up for Douglass a new way of life and new opportunities, he also left his own mark in New Bedford. He, along with other slave fugitives, stamped New Bedford as being a haven for slaves during the rocky time in our country’s history when battles were raging over the different ideals people held regarding race and slavery.

Douglass went on to become a well known orator, speaking nationally (as well as in Ireland and Great Britain) against slavery, sometimes even risking his life for this. He endured insults and threats, was often tired and lonely, but he never forgot his end goal. Douglass also became an advisor, political ally and friend to six presidents. He worked with and was a friend to abolitionists, women’s suffrage leaders, such as Susan B. Anthony, and authors, such as Ralph Waldo Emerson. He was a writer, publisher, speaker, preacher and political activist; from his selfless work others after him have felt the impact of the blessings he brought to the framework of America.

New Bedford Guide Your Guide to New Bedford and South Coast, MA

New Bedford Guide Your Guide to New Bedford and South Coast, MA